- Welcome to the Hiroshima City Virtual Emigration Museum

- The Beginning of Emigration from Hiroshima

- About This Site

Welcome to the Hiroshima City Virtual Emigration Museum

Ever since the S.S. City of Tokio departed for Hawaii in 1885 (Meiji 18) carrying the first government-sponsored immigrants, a large number of people have left Hiroshima to journey abroad to countries such as the United States of America, Canada, Peru, and Brazil. They left in such numbers that Hiroshima became the prefecture with the most emigrants in Japan. More than a century has passed since the first immigrants from Hiroshima set off for new lands, and today many people of Japanese descent are thriving around the world.

Since the start of materials collections in 1983 (Showa 58), the City of Hiroshima has amassed a number of materials related to emigration thanks to the support and understanding of countless people, many of whom are from Hiroshima Prefecture. In 2006 (Heisei 18), together with the Japanese Overseas Migration Museum established by the Japan International Cooperation Agency Yokohama, our city opened the Hiroshima City Virtual Emigration Museum online, making donated materials such as pictures of the times, and tools and daily goods actually used by immigrants publically accessible. It is our hope that you will deepen your understanding of how immigrants spent their everyday lives and overcame adversities, in addition to how their Japanese culture blended with the culture where they settled.

More than 130 years have passed since the departure of the first government-sponsored immigrants, and as time moves on, we have fewer and fewer opportunities to access firsthand accounts from the people who actually lived them. We hope that the Hiroshima City Virtual Emigration Museum will help you understand and convey the history of immigrants from Hiroshima and other prefectures to coming generations, with many invaluable materials.

We would like to express our sincere thanks to everyone who has supported this project by donating their priceless keepsakes, and through the sharing of stories and precious memories.

The City of Hiroshima

* Titles have been omitted from the names appearing on this website.

Supervising editors:

Tomonori Ishikawa, Professor Emeritus at University of the Ryukyus

Noriko Shimada, Professor Emeritus at Japan Women’s University (Hawaii Section)

Explanatory Notes

Japanese Eras

Western calendar years corresponding to Japanese eras are defined as follows:

The Meiji Era: 1868 – 1912

The Taisho Era: 1912 – 1926

The Showa Era: 1926 – 1989

The Heisei Era: 1989 – 2019

Bibliography

The content for this website is based on information from contributors and the sources listed below.

The Beginning of Emigration from Hiroshima page

Hiroshima Prefecture. Hiroshima-ken ijūshi tsūshi hen. Hiroshima Prefecture, 1993.

Hiroshima Prefecture. Hiroshimakenshi kindai 1. Hiroshima Prefecture, 1980.

Japanese Overseas Migration Museum. “Migration statistics by Prefecture.” Japanese Overseas Migration Museum Guide to Exhibits: Dedicated to Those Japanese Who Have Taken Part in Molding New Civilizations in the Americas. Yokohama: Japan International Cooperation Agency Yokohama International Center, 2015. p. 13.

Kodama, Masaaki. Nihon iminshi kenkyu josetsu. Keisuisha, 1992.

Hawaii section

Asahi Shimbun Hiroshimashikyoku. Bakushin: Nakajima no sei to shi. Tokyo: Asahi Shimbun, 1986.

Hibaku Kenzōbutsu Chōsa Kenkyūkai. Hibaku 50-shūnen Hiroshima no hibaku kenzōbutsu wa kataru: mirai e no kiroku (Architectural Witnesses to the Atomic Bombing: A Record for the Future). Hiroshima: Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, 1996.

Hiroshima Prefecture. Hiroshima-ken ijūshi shiryō hen. Hiroshima Prefecture, 1991.

Hiroshima Prefecture. Hiroshima-ken ijūshi tsūshi hen. Hiroshima Prefecture, 1993.

Hiroshima Prefecture. Hiroshimakenshi kindai 1. Hiroshima Prefecture, 1980.

Honolulu Hiroshima Kenjinkai. Honoruru Hiroshima kenjinkai kaiin meibo (Membership Directory 1971). Honolulu: Honolulu Hiroshima Kenjinkai, 1971.

Kawakami, F. Barbara. Hawai Nikkei imin no fukushokushi: kasuri kara palaka e (Japanese Immigrant Clothing in Hawaii, 1885-1941). trans. Yoichiro Katsuki. Tokyo: Heibonsha, 1998.

Kimura, Yoshigoro and Tanefumi Inoue. Saishin seikaku Hawai tokō annai. Tokyo: Hakubunkan, 1904.

Odo, Franklin and Kazuko Shinoto. Zusetsu Hawai Nihonjinshi 1885-1924 (A Pictorial History of the Japanese in Hawai’i 1885-1924). Honolulu: Hawai’i Immigrant Heritage Preservation Center, Department of Anthropology, Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, 1985.

Shimada, Noriko. “Hawai bon odori ni mirareru dentō bunka no keishō: Iwakuni ondo no kēsu o chūshin ni (Cultural Continuity Seen in Hawaii’s Traditional Bon Dance: The Case Study of Iwakuni Ondo).” JICA Yokohama Kaigai Ijū Shiryōkan kenkyū kiyō 9 2014-nendo (Journal of the Japanese Overseas Migration Museum JICA Yokohama Vol. 9 2014). Yokohama: Japanese Overseas Migration Museum, 2015. pp. 1-19.

Society for MINGU of Japan. “Oshigiri,” “Kōri,” “Hinoshi.” Nihon mingu jiten. Tokyo: Gyosei, 1997. pp.84, 198, 478.

Tasaka, Jack Y. Nihonjin kanyaku imin 100-nen sai kinen Hawai bunka geinō 100-nen shi (A Hundred Year History of Japanese Culture and Entertainment in Hawaii). Honolulu: East West Journal, 1985.

United Japanese Society of Hawaii. Zōho saihan Hawai Nihonjin iminshi (A History of Japanese Immigrants in Hawaii: Second edition with a Supplement). Honolulu: United Japanese Society of Hawaii, 1977.

Fukushima Prefectural Board of Education. “Arai Sekizen.” Utsukushima denshi-jiten. (accessed Jun., 2006).

The US mainland section

Beikoku Seihoku-bu Hiroshima Kenjinkai. Sōritsu 20-nen kinen ken no hitobito. Seattle: Beikoku Seihoku-bu Hiroshima Kenjinkai, 1920.

Hiroshima Prefecture. Hiroshima-ken ijūshi tsūshi hen. Hiroshima Prefecture, 1993.

Hokubei Senryu Ginsha. Hokubei senryū 12-gatsu-gō 1986: dai 42-kan dai 12-gō tsūkan 494-gō. Olympia: Hokubei Senryu Ginsha, 1986.

Iino, Masako. Mō hitotsu no Nichibei kankeishi. Tokyo: Yuhikaku Publishing, 2000.

Ito, Kazuo. Amerika shunjū 80-nen: Shiatoru Nikkeijinkai sōritsu 30-shūnen kinenshi. Seattle: Seattle Japanese Community Service, 1982.

Ito, Kazuo. Hokubei hyakunenzakura. Seattle: Japanese Community Service, 1969.

Kato, Shinichi. Beikoku Nikkeijin hyakunenshi: zaibei Nikkeijin hatten jinshiroku. Los Angeles: New Japanese American News, 1961.

Kikumura-Yano, Akemi. Amerika Tairiku Nikkeijin hyakkajiten: shashin to e de miru Nikkeikjin no rekishi (Encyclopedia of Japanese Descendants in the Americas: An Illustrated History of the Nikkei). trans. Masayo Ohara. Tokyo: Akashi Shoten, 2002.

Kimura, Yoshigoro and Tanefumi Inoue. Saishin seikaku Hawai tokō annai. Tokyo: Hakubunkan, 1904.

Kodaira, Naomichi. Amerika kyōseishūyōsho: sensō to Nikkeijin. Machida: Tamagawa University Press, 1980.

Momii, Ikken. 1952-nendo zenbei Nikkeijin jūshoroku (1952 Year Book). New Japanese American News, 1951.

Takeda, Jun’ichi. Zaibei Hiroshima kenjinshi. Los Angeles: Zaibei Hiroshima Kenjinshi Hakkōjo, 1929.

Takeuchi, Kōjiro. “Beikoku seihoku-bu zairyū hōjin meikan.” Beikoku seihoku-bu Nihon iminshi gekan (A History of Japanese Immigrants in Northwestern United States). Tokyo: Yushodo Press, 1994.

Zaibei Nihonjinkai. Zaibei Nihonjinshi. San Francisco: Zaibei Nihonjinkai, 1940.

Bainbridge Island Japanese American Community. BIJAC. (accessed Jun. 23, 2016).

Japanese American National Museum. “Hirasaki nashonaru risōsu sentā (Hirasaki National Resource Center).” Zenbei Nikkeijin hakubutsukan (Japanese American National Museum). (accessed Jun. 23, 2016).

Light House. “Nikkei butai no katsuyaku.” Light House Los Angeles. (accessed Sept. 8, 2006).

Canada section

Asami, Michiko, et al. Kanada ni watatta paionia: 21-seiki o hiraku kodomotachi e. Shinnan’yō: Kanada Nikkei Issei o Kangaerukai, 1987.

Hiroshima Prefecture. Hiroshima-ken ijūshi tsūshi hen. Hiroshima Prefecture, 1993.

Iino, Masako. Nikkei Kanadajin no rekishi (A History of Japanese Canadians: Swayed by Canada-Japan Relation). Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 1997.

Japanese Canadian Centennial Project. Senkin no yume: Nikkei Kanadajin hyakunenshi (A Dream of Riches: The Japanese Canadians 1877-1977). Toronto: Japanese Canadian Centennial Project, 1977.

Shimpo, Mitsuru. Kanada Nihonjin imin monogatari. Tokyo: Tsukiji Shokan Publishing, 1986.

Shimpo, Mitsuru. Nihon no imin: Nikkei Kanadajin ni mirareta haiseki to tekiō. Tokyo: Hyoronsha, 1977.

Koryo High School. “Gakkō no yurai.” Kōryō Gakuen Kōryō Kōtōgakkō. (accessed Sept. 25, 2006).

National Association of Japanese Canadians. Nikkei Kanadajin no kako to genzai (Japanese Canadians Then & Now). (accessed Jun. 19, 2006).

Vancouver Golden Stay Club. “Asahi Bēsubōru Chīmu.” Vancouver Golden Stay Club. (accessed Jun. 19, 2006).

Brazil section

Aoyagi, Ikutaro. “Burajiru ni okeru Nihonjin hattenshi jōkan.” Nikkei imin shiryōshū Nanbei hen dai 29-kan Shōwa senzenki hen 2. Tokyo: Nihon Tosho Center, 1999.

Associação Cultural Nipo Brasileira de Castanhal. Kasutanyāru Nippaku Bunka Kyōkai 20-nenshi. Associação Cultural Nipo Brasileira de Castanhal, 1986.

Associação Pan Amazônia Nipo Brasileira. Amazon chiiki ni okeru hōjin ijū no ayumi: ijū 55-shūnen kinengō. Associação Pan Amazônia Nipo Brasileira, 1984.

Associação Pan Amazônia Nipo Brasileira de Castanhal. Kasutanyāru hōjin kaitaku 50-nen no ayumi (Cinquenta Anos de Integração Rural Niponica em Castanhal). Associação Pan Amazônia Nipo Brasileira de Castanhal, 1975.

Cotia Seinen Renraku Kyoguikai. Kochia seinen ijū 30-nenshi. Sao Paulo: Cotia Seinen Renraku Kyoguikai, 1985.

Hamada, Kantaro. “Nanbei jitsujō to imin no kokuhaku.” Nikkei imin shiryōshū Nanbei hen dai 10-kan Meiji-Taishōki hen. Tokyo: Nihon Tosho Center, 1998.

Handa, Tomoo. Imin no seikatsu no rekishi: Burajiru Nikkeijin no ayunda michi. Sao Paulo: Centro de Estudos Nipo Brasileiros, 1970.

Hayashiuchi, Takeo. Nanbei no ibuki: Hiroshimakenjin o tazunete. 1971.

Hiroshima Prefecture. Hiroshima-ken ijūshi tsūshi hen. Hiroshima Prefecture, 1993.

Japan International Cooperation Agency. Gyōmushiryō No.891 kaigai ijū tōkei Shōwa 27-nendo-Heisei 5-nendo. Japan International Cooperation Agency, 1994.

Kakuda, Yoshito. Sōritsu 10-shūnen kinen Burajiru Hiroshima Kenjin hattenshi narabini kenjin meibo. Sao Paulo: Brasil Hiroshima Kenjinkai, 1967.

Kooyama, Rokuro. Kooyama Rokuro kaisōroku. Sao Paulo: Centro de Estudos Nipo-Brasileiros, 1976.

Nagata, Shigeshi. “Burajiru ni okeru Nihonjin hattenshi gekan.” Nikkei imin shiryōshū Nanbei hen dai 30-kan Shōwa senzenki hen 2. Tokyo: Nihon Tosho Center, 1999.

Nihon Imin 80-nenshi Hensan Iinkai. Burajiru Nihon imin 80-nenshi. Imin 80-nensai Saiten Iinkai and Brajiru Nihon Bunka Kyōkai, 1991.

Sociedade Civil Hiroshima Kenjin-kai do Brasil. Geibi dai 11-gō. Sao Paulo: Sociedade Civil Hiroshima Kenjin-kai do Brasil, 1972.

Takahashi, Yukiharu. Nikkei Burajiru iminshi. Tokyo: San-Ichi Publishing, 1993.

Yaeno, Matsuo. “Konnichi no Burajiru.” Nikkei imin shiryōshū Nanbei hen dai 12-kan Shōwa senzenki hen. Tokyo: Nihon Tosho Center, 1999.

Yasunaka, Suejirō. Burajiru takushoku kumiai keiei Basutosu ijūchi shashinchō (Album Fazenda Bastos: Commemoração do 10º Anniversarío 1938). Suejirō Yasunaka, 1938.

Kadowaki, Saori. “Nipponbunka o odorō! Burajiru ni ikiru kyōdogeinō dai 4-kai Hiroshima kenjinkai kaguramai e no jōnetsu otoroezu kōreika mo josei no katsuyaku medatsu.” Nikkey Shimbun. Aug. 20, 2003. (accessed Feb. 7, 2007).

Mitsui O.S.K. Passenger Line. “Sengo – MOPAS setsuritsu.” Nippon-maru kōshiki pēji. (accessed Jan. 31, 2007).

Okamoto, Gen. “Kagura runessansu dai 3-bu nōson no idenshi 3. kai Brajiru imin kyōshū no mai.” Chugoku Shimbun. Jun. 9, 2005. (accessed Feb., 2007).

Peru section

Andesu e no kakehashi: Nihonjin Perū ijū 80-shūnen kinenshi. Lima: Nihonjin Perū Ijū 80-shūnen Shukuten Iinkai, 1982.

Chugoku Shimbun Imin shuzai han. Imin: Chūgoku Shinbun sōkan 100-shūnen kinen kikaku. Hiroshima: Chugoku Shimbun, 1992.

Hiroshima Prefecture. Hiroshima-ken ijūshi tsūshi hen. Hiroshima Prefecture, 1993.

Inamura, Tetsuya. “Menka-ō Okada Ikumatsu: Perū Nihonjin imin to asienda.” Kikan minzokugaku 88-gō. Suita: Senri Foundation, 1999. pp. 44-55.

Ito, Tsutomu and Isamu Goya. Zai Perū hōjin 75-nen no ayumi 1899-nen-1974-nen (Inmigracion Japonesa al Peru 75 Aniversario 1899-1974). Lima: Perú Shimpo, 1974.

Konno, Toshihiko and Yasuo Fujisaki. Iminshi 1 Nanbei hen. Tokyo: Shinsensha, 1984.

Miyake, Masaomi. “Nanbei no Nikkei shakai: ken shusshin no ijūsha-tachi 7.” Chugoku Shimbun. Jun. 30, 1979.

Mizuno, Ryo. Nanbei Perū oyobi Boribia shashinchō (Album Gráfico é Informativo del Perú y Bolivia). Lima: Nippi Shimpo, 1924.

Perū Chūō Nihonjinkai Hensan Iinkai. Chūnichikai 50-nen no ayumi: Perū Chūō Nihonjinkai sōritsu 50-shūnen kinenshi. Lima: Sociedad Central Japonesa del Peru, 1967.

Raten Amerika Kyōkai. Nihonjin Perū ijū no kiroku. Tokyo: Raten Amerika Kyōkai, 1969.

Society for MINGU of Japan. “Kairo.” Nihon mingu jiten. Tokyo: Gyosei, 1997. p.102.

Tomita, Ken’ichi and Tomoji Kageyama. “Nanbei Perū: Daitōryō Regīa Perū to Nihon.” Nikkei imin shiryōshū Nanbei hen dai 8-kan Meiji-Taishōki hen. Tokyo: Nihon Tosho Center, 1998.

Yamada, Tatsumi. Nanbei Perū to Hiroshima kenjin. Lima: Perū Hiroshima Kenjinkai, 1931.

Yanaguida, Toshio. Rima no Nikkeijin: Perū ni okeru Nikkei shakai no takakuteki bunseki (La Colectividad Peruano Japonesa en Lima: Investigación multidisciplinaria 1995). Tokyo: Akashi Shoten, 1997.

Yanaguida, Toshio and Yutaka Yoshii. Perū Nikkeijin no 20-seiki: 100 no jinsei 100 no shōzō. Tokyo: Fuyo Shobo Shuppan, 1999.

Sagamihara-shi Tsukui Kyōdo Shiryōshitsu. “Senzen no kyōkasho yūmeina kyōzai: San’yūshi.” Tsukui Kyōdo Shiryōshitsu. (accessed Dec. 6, 2006).

Yamasaki, Shigeru. “Perū deno taiken kara: Rima Nihonjin-gakkō to Nikkeijin.” Shimane International Center, (accessed Dec., 2006).

The Beginning of Emigration from Hiroshima

Full-scale emigration from Hiroshima Prefecture had its origins in the emigration of the kanyaku imin, government-sponsored labor emigrants contracted under an agreement signed between the governments of the Kingdom of Hawaii and Japan, to Hawaii. The program ran from 1885 to 1894 (Meiji 18-27).

At the time, the sugarcane industry in Hawaii was flourishing, and there was a severe labor shortage. In response, a request was made to the Japanese government for more labor immigrants.

Since the Edo period (1603-1868), Hiroshima residents had traditionally ventured to distant lands in search of employment due to the prefecture’s mountainous terrain and lack of agricultural lands. As Japan entered the Meiji era (1868–1912), residents were impoverished by the economic decline in rural areas brought on by modernization policies, the loss of fishing grounds due to Ujina Port’s construction and natural disasters, etc. Applications poured in when recruitment for kanyaku imin commenced, and successful applicants were dispatched to Hawaii after going through a rigorous screening process.

Labor immigrants from Hiroshima and Yamaguchi enjoyed a good reputation for being honest and hardworking at the sugarcane plantations they were contracted to, which led to the regular recruitment of people from these two prefectures.

Labor immigrants brought their earnings from Hawaii back to Japan and used it to pay off debts and buy land and houses. One after another, Japanese private immigration companies started to emerge, and people began emigrating to the mainland United States, Canada, Latin America, and Oceania. The success enjoyed by these labor immigrants led to an abundance of people wanting to emigrate abroad, and this boom of seeking employment overseas continued even after the government-sponsored emigration program ended.

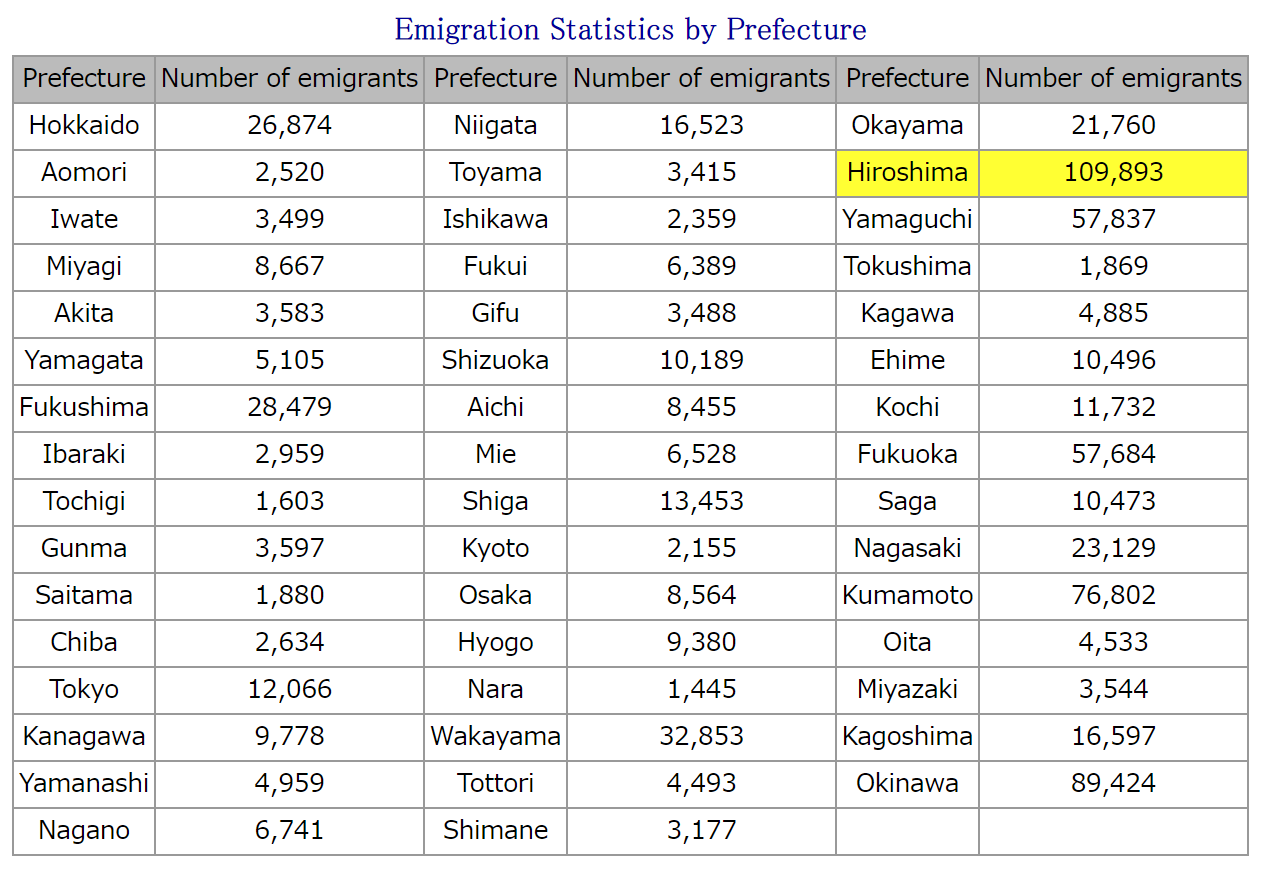

This data is the summary of the number of emigrants by prefecture from 1885 to 1894 (Meiji 18–27) and 1899 to 1972 (Meiji 32–Showa 47).

Source: Japanese Overseas Migration Museum. “Migration statistics by Prefecture.” Japanese Overseas Migration Museum Guide to Exhibits: Dedicated to Those Japanese Who Have Taken Part in Molding New Civilizations in the Americas. Yokohama: Japan International Cooperation Agency Yokohama International Center, 2015. p.13.

About This Site

Terms of Use

The images and text on this site are the property of the City of Hiroshima. (Some of the materials are still in the care of the original author or owner.) The City of Hiroshima prohibits the use, reproduction, transfer, sale, modification, printing or distribution of any part of the website, except for fair use in accordance with the copyright law.

All images on this site have been embedded with a digital watermark.

If you wish to use any material from this site, please contact the Cultural Promotion Division of the City of Hiroshima.

Contact Us

If you have any questions about this site, please contact:

Cultural Promotion Division

Culture and Sports Department

Citizens Affairs Bureau

The City of Hiroshima

1-6-34 Kokutaiji-machi, Naka-ku, Hiroshima

Japan

730-8586

Tel: +81-(0)82-504-2500 / Fax: +81-(0)82-504-2066

Mail:bunka@city.hiroshima.lg.jp

Please be aware that it will take us some time to write you back if you contact us in a language other than Japanese.

© The City of Hiroshima 2020