Hiroshima City Virtual Emigration Museum : Hawaii section

- From Government-sponsored Immigrants to Private-sponsored Immigrants, Free Immigrants, and Summoned Immigrants

- Sugarcane Plantation Labor and Expansion into the Cities

- The Formation of Japanese American Societies

- Anti-Japanese Sentiment and the Pacific War

- The Life of Immigrants in the Multicultural Society of Hawaii

From Government-sponsored Immigrants to Private-sponsored Immigrants, Free Immigrants, and Summoned Immigrants

Courtesy of Junpei Toma

In 1885, full-scale immigration to Hawaii began under the agreement between the government of Japan and the Kingdom of Hawaii, starting with government-sponsored contract labor immigrants. At the time, the sugarcane industry was flourishing and there was a severe labor shortage in Hawaii. Following the first voyage of the immigrant ship City of Tokio, 26 voyages took place over the next ten years, carrying a total of around 29,000 immigrants, of whom more than 11,000, or 38.2 percent, were from Hiroshima Prefecture.

In 1893, the Kingdom of Hawaii was overthrown by American settlers, and in 1894 the Japanese government turned emigration over to licensed private companies. The immigrants, then, were called private-sponsored immigrants, and numbered over 40,000 in total.

Then, in 1898 Hawaii was annexed by the U. S. and in 1900, when Hawaii was incorporated as a U.S. territory, contract labor was prohibited. Immigrants from 1900 on were free immigrants not bound by contracts, and this wave of immigration, totaling about 68,000, continued until the U.S.-Japan Gentlemen’s Agreement was enacted in 1908. The agreement restricted new immigration to immediate family, including “picture brides,” summoned by those already in the U. S. Approximately 62,000 were summoned to Hawaii until the Immigration Act of 1924 banned any immigrants from Japan.

In 1924 over 30,000 people originating from Hiroshima Prefecture lived in Hawaii, making up the largest segment of the Japanese population.

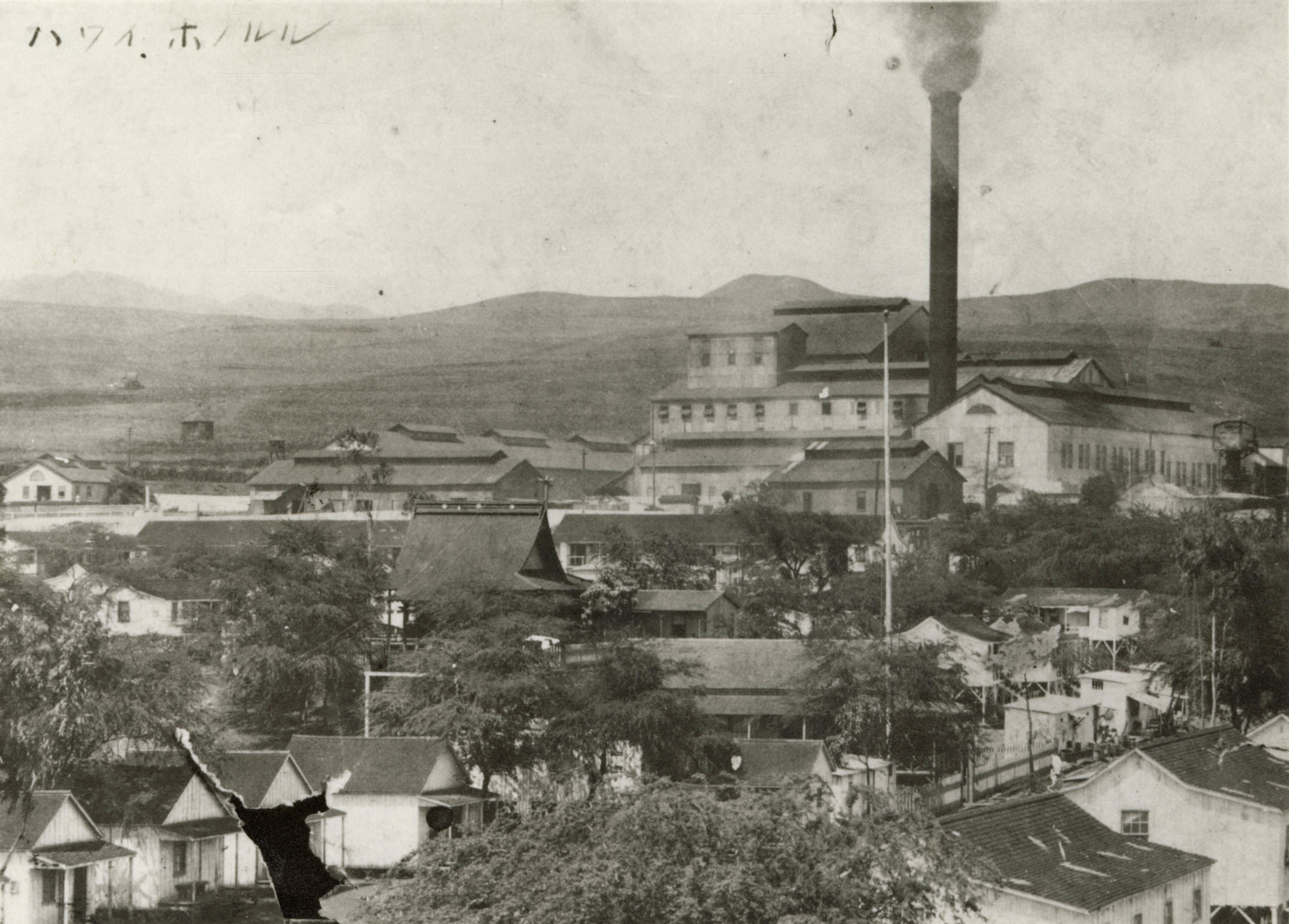

Sugarcane Plantation Labor and Expansion into the Cities

The City of Hiroshima

During the early period, Japanese emigration to Hawaii was nothing more than a way to earn some money to make a triumphant return home, and life in Hawaii was considered no more than a temporary stay. During the time of government-sponsored immigrants in particular, the immigrants scattered to their contracted plantations soon after they arrived in Hawaii, and spent all their days in harsh labor. Immigrants were forced to work long hours and performed physically intense labor, cutting and carrying sugarcane under the relentless Hawaiian sun and often getting cut by the sharp edges of the sugarcane leaves.

The Japanese laborers adapted their kimono to fit their labor conditions, drawing on ideas from the clothing of other laborers and from traditional Japanese work clothes such as hand coverings and leggings.

Soon, many Japanese laborers headed to large cities such as Honolulu and Hilo in search of greater success. Many were engaged in technical vocations such as hairdressing, carpentry, and tailoring, others operated businesses such as restaurants, hotels, trading companies and farms. Some also found employment in the homes of white families.

Kona coffee harvested in Kona, Hawaii Island has a strong aroma, and is produced in small quantities, making it well-known as a high-class item. When the price of coffee plummeted worldwide in 1900, Japanese immigrants took over its cultivation, a situation which continues to the present day.

The Formation of Japanese American Societies

Courtesy of Junpei Toma

During the free immigration period, travel and medical expenses were to be covered by the immigrants, and it became difficult to make enough money to make a triumphant return home. Many immigrants ended up living in Hawaii while sending money back to their families. In the period of summoned immigration, there were many cases of immigrants having a bride introduced to them through photograph exchange with their families back home and sent over to them to build a family ? a process called “picture marriage.” When the Immigration Act of 1924 prohibited Japanese immigrants from entering the country, migrant workers tended more and more to settle permanently in Hawaii.

The second generation born in Hawaii attended local public schools and tended to speak English rather than Japanese, making it hard to communicate with their parents. Japanese language schools were established all over the islands, and parents sent their children to these schools after their regular school time in preparation for an eventual return to Japan, and so that they would not forget their homeland.

Many Japanese language newspapers were also published, such as the Nippu Jiji and the Hawaii Hochi. Also, many Buddhist temples, Christian churches, and the Hawaii Nihonjin-kai (Japanese Associations of Hawaii) were established, and Japanese American societies developed.

In 1898, immigrants from Hiroshima Prefecture established the Hiroshima Kenjin Gokyukai (Society for the Mutual Benefit and Assistance of Immigrants from Hiroshima Prefecture). Based on a news dispatch from Hawaii, the Geibi Nichinichi Shimbun in Hiroshima published an article celebrating the banding together of immigrants from Hiroshima Prefecture, referencing the history of famous feudal lord Mori Motonari. In addition, exchanges with the homeland were promoted by sending groups of visitors to Hiroshima.

Anti-Japanese Sentiment and the Pacific War

Courtesy of Kikue Kato

On the United States mainland, with the abrupt increase in Japanese immigrants and due to anti- Japanese sentiment, it became difficult to get authorization to enter the mainland. This led many Japanese to immigrate first to Hawaii, and then to migrate to the mainland. In 1907, however, a restriction was imposed on this kind of migration. Then in 1908, the Gentlemen’s Agreement between the U.S. and Japan prohibited immigration of Japanese laborers with the exceptions of those who had immigrated previously and were now returning, and relatives of Japanese migrants currently residing in the United States. Then complaints arose against “picture marriage,” and with the rising economic competition, anti-Japanese sentiment grew further, leading to the enactment of the Immigration Act of 1924.

In Hawaii, Japanese laborers held large-scale strikes on plantations on Oahu Island in 1920, demanding higher wages. Japanese then filed a lawsuit in 1922 to protest the laws legislated around the same time to regulate or restrict Japanese language schools. As a result of these events, on the Hawaiian islands where racial relations had been peaceful compared to those on the mainland, anti-Japanese tensions arose.

In the latter half of the 1930s, as the relationship between Japan and the U.S. deteriorated, Japanese Americans found themselves torn between their homeland, Japan, and their country of residence, America. After the Pacific War broke out, some of the Japanese leaders in Hawaii (0.9% of the Japanese American population) were relocated to internment camps in mainland America. Hawaii’s Nisei proved their patriotism by volunteering for the all Nisei 100th Infantry Battalion and being conscripted for the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. As a result many Japanese Americans died in action.

The Life of Immigrants in the Multicultural Society of Hawaii

Photographed by Kazuhisa Tahara

Sugarcane plantation workers in Hawaii consisted of not only Japanese, but of those from other countries such as China, Portugal, Puerto Rico, Korea and the Philippines, who all worked together side-by-side. There, “local” culture was born. For example, workers got into the habit of sharing food from the box lunches they each brought to work. This practice of mixing rice and a variety of ethnic foods became known as mixed plate and is still enjoyed today. This mixing of cultures in Hawaii has brought about, on the foundation of Hawaii’s traditional “Aloha spirit,” the spirit of tolerance toward different cultures, resulting in the formation of a unique culture of Hawaii. Especially after WWII, the rate of inter-marriage among different ethnic groups, including Japanese Americans, was high – which led to a diversification of ways of life.

On the other hand, the Japanese immigrants also had pride in Japanese culture and dedicated efforts to its preservation. Newspapers and television/radio broadcasts in Japanese are still an integral part of the region’s lifestyle. Events such as Bon dances and the floating of lanterns in summer, or rice cake pounding, osechi-ryori, and hatsumode during New Year are still widely enjoyed each year. There are also some aspects of Japanese culture that have become an integral part of local Hawaiian culture, such as removing one’s shoes before entering a home.